In 1830, Congress passed President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act, authorizing the President to negotiate removal treaties with Indian tribes living in the eastern United States. These "voluntary" treaties would offer federal land west of the Mississippi River in exchange for Indian land in the east, and provide assistance with the tribe's relocation.

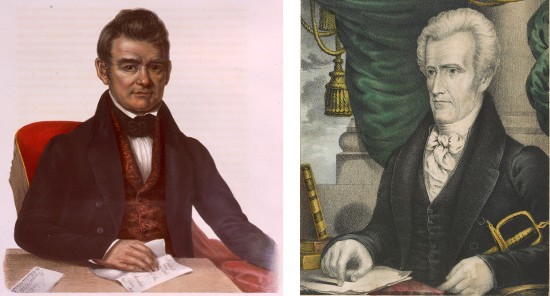

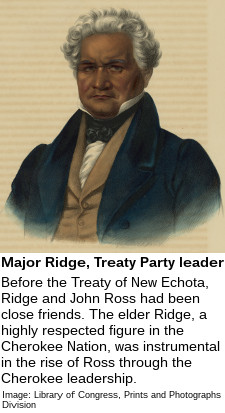

The Cherokee Nation under Principal Chief John Ross resisted attempts by Andrew Jackson's administration to induce the tribe to accept a removal treaty. In 1832 the U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling in the case of Worcester vs. Georgia that should have protected the Cherokee from a series of oppressive laws passed by the state of Georgia intended to destroy the tribe as an independent political entity, but Jackson avoided his duty as Chief Executive and refused to enforce the Court's decision. As a result of Jackson's malfeasance, several Cherokee leaders, led by the respected statesman Major Ridge, became convinced that removal was inevitable and that the Cherokees should accept a removal treaty. Ridge and his followers became known as the Treaty Party.

In December of 1835, even though they weren't elected representatives of the Cherokee national government, the Treaty Party leaders signed the Treaty of New Echota, which stipulated the Cherokee would emigrate to the west within two years. A majority of Cherokees did not accept the Treaty of New Echota as a legitimate agreement - more than 90 % signed a petition opposing it, and the treaty was never ratified by the elected government of the Cherokee Nation. The U.S. Senate ratified it anyway - by one vote, after much public outcry - and in May, 1836 Jackson signed it into law.

During the next two years, Chief John Ross tried to convince Congress to nullify the Treaty of New Echota, presenting memorials and petitions against it. Meanwhile, the United States began a military occupation of the Cherokee Nation. In July, 1836, General John E. Wool took command of the "Army of East Tennessee and the Cherokee Nation", consisting of 1,000 volunteers from Tennessee. They repaired roads, built forts and stockades, and marched through towns in a display of force meant to shock and awe the population into submission. Wool began disarming the Cherokees and tried to neutralize Ross's resistance efforts through verbal persuasion in meetings, written proclamations, and physical intimidation, at one point detaining some Cherokee leaders who attended a council called by Wool in North Carolina.

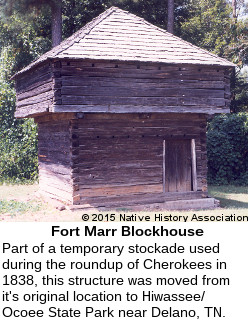

In 1837 Martin Van Buren succeeded Andrew Jackson as President and continued the Indian Removal policies of Jackson's administration. Many Cherokees were already being forced off their property by local residents. General Wool made an effort to stop the illegal seizure of Cherokee property, and he also offered food and clothing to any Cherokees that would enroll for emigration. Most refused, fearing this would be construed as accepting the New Echota treaty. During the year, and into the spring of 1838, several groups of Cherokees, including Major Ridge and other Treaty Party leaders and supporters, did leave for Indian Territory, but most continued to resist the coercion of federal and state officials aimed at preparing them for removal. The federal government continued with plans to make the Cherokee move by force, building more stockades and large keelboats to be used to transport the Cherokees by water.

General Wool was relieved from his command on July 1, 1837 after a series of conflicts with his superiors and civilian officials in charge of the removal. His replacement, Colonel William Lindsay, continued to build forts, organize militia, and collect supplies.

In April, 1838, a delegation led by Chief John Ross presented a memorial to Congress protesting the Treaty of New Echota signed by 15,665 Cherokees, but it was rejected. As the removal deadline approached, Senators and Representatives continued to submit petitions from thousands of their constituents asking that the treaty not be enforced. Newspapers printed editorials and letters from readers supporting the Cherokee. Raplh Waldo Emerson wrote an open letter to President Van Buren calling the impending Cherokee removal a "crime" that would cause the name of the United States to "stink to the world."

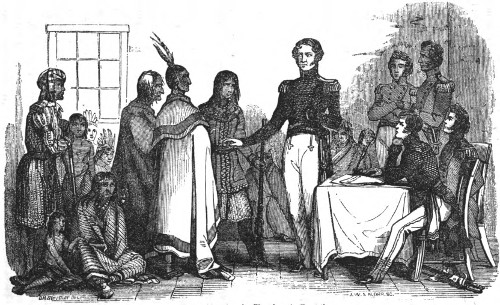

The deadline set by the Treaty of New Echota for the Cherokees to move was May 23, 1838. On April 6, General Winfield Scott of the United States Army received orders to proceed to the Cherokee Agency near present-day Charleston, Tennessee and take command of the "Army of the Cherokee Nation". He would have 2,200 regular soldiers and access to militia from Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and North Carolina, bringing the size of the force to over 7,000. He arrived at the Agency on May 8, and two days later he met with Cherokee leaders to tell them he was there to enforce the treaty and it was time for them to emigrate.

On May 17, 1838, Scott issued Order 25. It divided the Cherokee Nation into Eastern, Western, and Middle military districts and directed his forces to capture and transport the Cherokees to Fort Cass (Charleston) or Ross's Landing (present-day Chattanooga) in Tennessee, or Gunter's Landing (present-day Guntersville) in Alabama, after the May 23rd deadline had passed. To prevent "general war and carnage" it also ordered that "every possible kindness ... be shown by the troops" and made it the "special duty" of every officer and man to make sure this stipulation was followed to uphold "their own honor and that of their country." To prevent Cherokee resistance, the army should "get possession of the women and children first, or first capture the men" so the rest of the family would comply. Families in the Army's "possession" were not to be separated. Cherokee men were to be guarded and escorted unless "their women and children are safely secured as hostages". Some Cherokees also held African American slaves, who would be "treated in like manner as the Indians themselves."

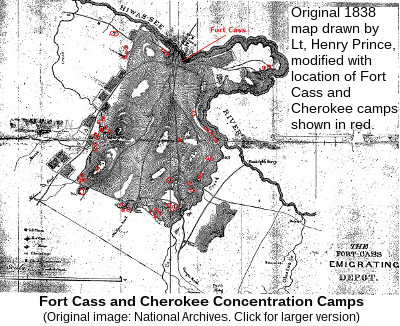

After the deadline passed on May 23, 1838, the Cherokee roundup began. During the rest of the spring and early summer, U.S. forces hunted Cherokee people down, took them prisoner, and marched them to temporary stockades in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee. Later they were moved to concentration camps in and around present day Charleston, Tennessee and Fort Payne, Alabama.

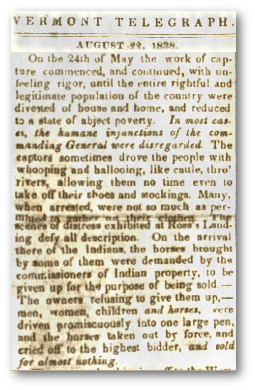

General Scott's later accounts of the roundup relate that his orders were followed and the operation was done with kindness, and some of his men even had "flowing tears". This may have been true for the soldiers under his close supervision, but newspaper reports like the Vermont Telegraph news item from August 22, 1838, shown at left, tell a different story: "In most cases, the humane injunctions of the commanding General were disregarded." This is corroborated by many eyewitness accounts. In the 19th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, James Mooney gives a description of the round up compiled from Cherokee captives and white witnesses, including some of the soldiers: "Families at dinner were startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway and rose up to be driven with blows and oaths along the weary miles of trail that led to the stockade." In a letter written from one of the concentration camps in June, 1838, missionary Evan Jones, who later traveled with one of the detachments to the west, said "multitudes were allowed no time to take anything with them, except the clothes they had on." General Scott himself admitted in a letter written to General Nathaniel Smith, Superintendent of Cherokee Emigration, on June 8, 1838, that many Cherokees had not been allowed to take "bedding, cooking utensils, clothes and ponies", all items General Order 25 had specified that they be allowed to "collect and take with them".

Some Cherokees avoided the round up, at least for a while. Hundreds hid in the mountains of Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina as the military dragnet swept towards their homes, and some escaped from the holding pens. In August, 1838, General Scott assigned units of mounted troops that continued to hunt the fugitives into the fall.

The Oconaluftee Citizen Indians also were not included in the round up. They were a group of about 60 Cherokee families led by Chief Yonaguska who were exempt from forced removal. They had given up their Cherokee citizenship under the terms of the Cherokee Treaties of 1817 and 1819, which granted them individual tracts of land near the Oconaluftee River in North Carolina, outside the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. Another group of about 200 Cherokees in the North Carolina town of Cheoah also weren't removed, and with the help of three white men were able to buy 1,235 acres when Cherokee land was put up for sale in September, 1838.

As the stockades filled up during the late spring of 1838, the forced removal began. On June 6 the first detachment of between 600 and 800 Cherokees left from Ross's Landing under military escort, traveling on a series of steamboats, towing flatboats and keelboats, down the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, White, and Arkansas rivers to Fort Coffee in Indian Territory. They completed their trip in just under two weeks with relatively few problems and no reported deaths. Another detachment, numbering 846, left from Ross's landing on June 12, also traveling by boat under military escort and following the same river route as the first. A drought that affected much of the United States lowered water levels and stranded the boats on the Arkansas River more than 100 miles short of the destination, so the journey had to be completed over land, with water scarce and in extreme heat. They arrived in Indian Territory on August 5, 1838, with a death toll of 73, with most deaths occurring during the overland segment.

By the time the next detachment of approximately 1,070 people left on June 17, 1838, the Tennessee River was so low the Cherokees had to be marched from Ross's Landing to Waterloo, Alabama. On June 19, acting on a request from the Cherokee National Council and his own humanitarian concerns, General Scott suspended the removal until September 1, 1838, hoping the drought and the "sickly season" would be over by then. On receiving this news, the Cherokees en route to Waterloo petitioned Superintendent Smith to allow them to return to Ross's Landing, but he refused. The Cherokees were forced to continue and arrived at their destination on July 14, where their military escort boarded them onto a steamboat and a large keelboat. They were transported by the river route and ran aground on the Arkansas River near the same spot where the previous detachment had been stranded, and also had to complete their journey traveling overland, arriving at Fort Coffee on September 7, 1838. The final death toll for this group of Cherokees was 146.

During the summer of 1838, conditions in the concentration camps deteriorated as heat, overcrowding, poor food, and lack of shelter led to epidemics of dysentery and other diseases. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people died. A recent scholarly analysis estimates the number of deaths at 373. Elizur Butler, a physician and missionary who attended the Cherokees in the camps, estimated the number of deaths at 2,000.

In July, the Cherokee National Council submitted a proposal to General Scott asking that the Cherokee Nation be permitted to "undertake the whole business of removing their people to West of the river Mississippi", with a pledge that the emigration would start after the "sickly season should pass away." Scott agreed, with the stipulation that the Cherokees resume the removal by September 1.

Chief Ross and his advisers planned for the rest of the emigrating Cherokees to travel by land. General Scott provided 645 wagons, 5,000 horses and oxen, and a steamboat for those not able to travel overland. He then turned control of the removal over to Chief Ross. 13 groups, or detachments, were organized under Ross's direct supervision. Each detachment contained about 1,000 people, except for the last group which would include around 200 of the sickest Cherokees. Another detachment of about 600, led by John Bell, was composed mainly of members of the Treaty Party and not managed by Ross.

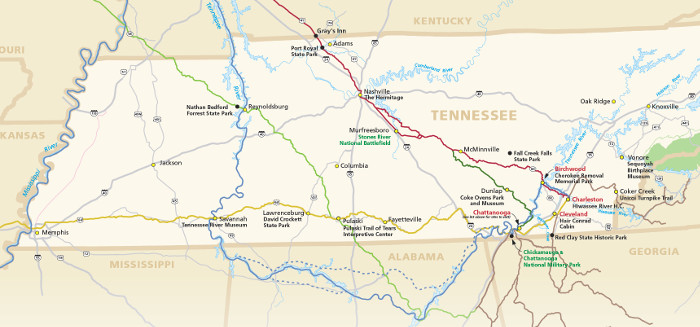

The planned route for most of the detachments supervised by Chief Ross, now known as the Northern Route, would take them from the Cherokee Agency area (present-day Charleston, Tennessee), through McMinnville and Nashville, then into Kentucky and Illinois, through southern Missouri to Arkansas, and on to Indian Territory. Two detachments, one of them led by Cherokee National Coucil President Richard Taylor, would take what is now called Taylor's Route and travel from Ross's Landing to near McMinnville, then follow the rest of the Northern Route. Another detachment would leave Fort Payne, Alabama, enter Tennessee and pass through Pulaski, then cross the Tennessee River at Reynoldsburg, continue on to western Kentucky, then through southeastern Missouri and northern Arkansas, to Indian Territory. This route is called Benge's Route for the leader of the detachment, John Benge. The Treaty Party detachment led by John Bell would travel from the Cherokee Agency area across southern Tennessee to Memphis, where they crossed the Mississippi River, then on through Arkansas to Indian Territory.

The wagons and horses were meant to be used for hauling food and other supplies, and for transporting people not able to walk. Most healthy Cherokees would make their way on foot. Supplies would also be stored at places like Nashville and bought at stores and mills along the way. Each detachment would leave a few days apart to give enough time to replenish the supply spots and to avoid depleting water sources.

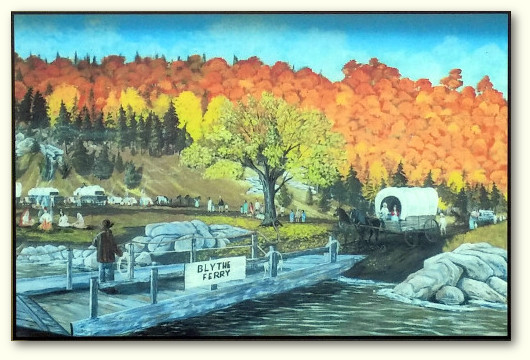

The Cherokees completed their preparations before the deadline and the first detachment; led by Hair Conrad, left from the Cherokee Agency on August 28, 1838. The second detachment, led by Elijah Hicks, followed on September 1. The first detachment traveled about 18 miles to Blythe's Ferry on the Tennessee River and started to cross, but the drought and heat wave persisted, making water supplies hard to find, so General Scott ordered a temporary halt to the removal. The first detachment then camped at the ferry on both sides of the river, while the second camped four miles away. Departures for the other detachments were also put on hold.

Rain in September allowed the emigration to resume and the detachments began to get underway again on October 1, 1838. Hair Conrad, the leader of the first detachment, had become ill and was replaced by Daniel Colston, causing a delay for this detachment, during which the second detachment, led by Elijah Hicks, crossed the Tennessee River at Blythe Ferry and became the lead detachment on the Northern Route. By the first week in November, all of the detachments that traveled overland were on the road towards Indian Territory. The last group of around 220, which included those unable to travel by land, as well as John Ross and his family, left by steamboat on the Hiwassee River from the Cherokee Agency area on December 5, 1838.

Sources

(Click to open/close the list)

"Message To Congress, December 8, 1829" by President Andrew Jackson,

Journal Of The House Of Representatives, published by the United States House of Representatives, 1829: pg. 23-25. Digitized by Google Books.

"An Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing

in any of the states or territories, and for their removal west of the river Mississippi" (The Indian Removal Act Of 1830),

United States Statutes At Large, Twenty-first Congress, First Session, Chapter 148, published by the United States Government Printing Office, pg. 411-412.

Register Of Debates In Congress Volume 6 Part 1 (Debate in the Senate from December 7, 1829 to May 31, 1830 and House of Representatives from

December 7, 1829 to March 24, 1830), published by Gales and Seaton, 1830. Digitized by Google Books.

Register Of Debates In Congress Volume 6 Part 2 (Debate in the House of Representatives from March 24, 1830 to May 31, 1830), published by Gales and

Seaton, 1830. Digitized by Google Books.

Speech of Mr. Everett, Of Massachusetts, On The Bill For Removing The Indians From The East To The West Side Of The Mississippi, by Representative

Edward Everett, published by Gales and Seaton, 1830. Digitized by Google Books.

Speech of Mr. Wilson Lumpkin, Of Georgia, On The Bill Providing For The Removal Of The Indians, by Representative Wilson Lumpkin, printed by Duff Green, 1830. Digitized by Google Books.

Worcester vs. Georgia 31 U.S. 515 (1832),

United States Supreme Court.

"The Cherokees vs. Andrew Jackson", by Brian Hicks, Smithsonian Magazine . March 2011.

"Treaty With The Cherokee, 1835" (Treaty of New Echota) Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Volume II, compiled and edited by Charles J. Kappler, Clerk

to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, published by the Government Printing Office, 1904. Digitized by Google Books.

Letter From John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation of Indians, In Answer To Inguiries From A Friend Regarding The Cherokee Affairs With The United

States, 1836. Digitized by Google Books.

"No. 744 Proceedings Of A Court Of Inquiry Relating To Transactions Of Brevet Bridagier General John E. Wool, And Those Under His Command, In The

Cherokee Country, In Alabama"

American State Papers Class V. Military Affairs. Volume VII. Commencing March 1,1837 and Ending March, 1838, Published by Gales and Seaton, Washington, 1861: pg. 532-571. Digitized by Google Books. Web. December 14, 2015.

Memorial Of A Delegation Of The Cherokee Nation Remonstrating Against the Instrument of Writing (treaty) of

December 1835, January 15, 1838. Printed by order of the House of Representatives, 1838. Internet Archive. Web. December 14, 2015.

"Memorial Of The Cherokee Delegation Submitting The Memorial and Protest of the Cherokee People To Congress, April 9, 1838",House Documents, Otherwise Published As Executive Documents, 25th Congress, 2nd Session, 1837-8, Document No. 316. Digitized by Google Books. Web. December 14, 2015.

For memorials submitted to Congress protesting Cherokee removal in 1838, see the Journal of the Senate

of the United States of America and the Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States for the 25th

Congress, 2nd Session, December, 1837 to July, 1838. (Search within these documents on "treaty of 1835" or "Cherokees"). Digitized by Google Books. Web. December 14, 2015.

"The Indians" and "The Cherokees", Vermont Telegraph, April 4, 1838, page 111. Chronicling America - Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress and National Endowment For The Humanities. Web. December 14, 2015.

"To Martin Van Buren, President of the United States", by Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Burlington Free Press, June 29, 1838, page 1. Chronicling America - Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress and National Endowment For The Humanities. Web. December 14, 2015.

"Letter From The Secretary of War Transmitting Copies of the

Correspondence between the War Department and Major General Scott, in relation to the Removal of the Cherokees, July 4, 1838",House Documents, Otherwise

Published As Executive Documents, 25th Congress, 2nd Session, 1837-8, Document No. 453. Digitized by Google Books. Web. December 14, 2015.

The Trail of Tears In Tennessee: A Study of the Routes Used During the Cherokee Removal of 1828. by Benjamin C. Nance, published by Department of Environment and Conservation Division of Archaeology 2001.

Myths of the Cherokee: Historical Sketch of the Cherokee, by James Mooney.

Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1895, page 130.

The Promised Land: The Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal, 1794-1839, by Charles Russell Logan, published by the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. 1997.

Voices From The Trail Of Tears, edited by Vicki Rozema, published by John F. Blair, Publisher, 2003.

Footsteps Of The Cherokees: A Guide To The Eastern Homelands Of The Cherokee Nation, by Vicki Rozema, published by John F. Blair, Publisher, 1995.

"The Trail of Tears and the Forced Relocation of the Cherokee Nation", Teaching with Historic Places Lesson Plans - American Indian History, National Park Service web site, accessed December 2015.

"Chaos In The Indian Country: The Cherokee Nation, 1828-35", by Kenneth Penn Davis, The Cherokee Indian Nation - A Troubled History, edited by Duane King, published by The University of Tennessee Press, 1979, pages 129-147.

"The Origin Of The Eastern Cherokees As A Social And Political Entity", by Duane H. King, The Cherokee Indian Nation - A Troubled History, edited by Duane King, published by The University of Tennessee Press, 1979, pages 164-180.

"The Cherokees. Extracts of letters from General Winfield Scott and Lieutenant A.J. Smith."

Niles National Register, From September, 1838 To March, 1839 - Vol. V 1839: pg. 204. Digitized by Google Books. Web. accessed December 14, 2015.

"Message From The President Of The United States To The Two Houses Of Congress, December 4, 1838" by President Martin Van Buren,

House Documents, Otherwise Published As Executive Documents: Twentyfifth Congress, Third Session, 1838: Document 2, pg. 15. Digitized by Google Books.

"Report Of The Secretary Of War, November 28, 1838" by Secretary of War J.R. Poinsett,

House Documents, Otherwise Published As Executive Documents: Twentyfifth Congress, Third Session, 1838: Document 2, pg. 101-102. Digitized by Google Books.

"Proposition Of Cherokee Delegation To General Scott, July 23, 1838" by John Ross, Elijah Hicks, James Brown, Edward Gunter, Samuel Gunter, Situwakee, White Path, and R. Taylor,

House Documents, Otherwise Published As Executive Documents: Twentyfifth Congress, Third Session, 1838: pg. 429-430. Digitized by Google Books.

"General Winfield Scott To John Ross, E. Hicks, J. Brown, E. Gunter, S. Gunter, Situwakee, White Path, and R. Taylor",

House Documents, Otherwise Published As Executive Documents: Twentyfifth Congress, Third Session, 1838: pg. 430-431. Digitized by Google Books.

"Trail Of Tears", directed by Joshua Colover, National Park Service, online video, accessed May 23, 2015.

"The Price Of Cherokee Removal", by Matthew T. Gregg and David M. Wishart, Explorations in Economic History available online July 2012.

Related Links

(Click to open/close the list)

The Indian Removal Act of 1830

The 1823 Nashville Toll Bridge

The Old Jefferson Site

Exile's Communion - Trail of Tears In Nashville

Thousands of Cherokees Passed Through La Vergne on Trail of Tears

Stones River National Battlefield

Pulaski / Giles County Trail of Tears Memorial

Port Royal State Historic Park

David Crockett State Park

Cherokee Removal Memorial Park

Red Clay - TN History for Kids

Moccasin Bend National Archeological District

Chickasaw Treaty Council Of 1830

Cherokee Heritage Sites In Southeast Tennessee

Trail of Tears Association

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail - National Park Service

Trail of Tears Tennessee Map and Guide - National Park Service brochure

Trail of Tears National Historic Trails Map.

Books: (The Native History Association is an Amazon Associate. If you buy using one of our Amazon Book links, we get a small percentage of the sale, and we appreciate that support.)